Lorelei Cloud grew up in a house without running water. Every week, her family would travel to her uncle’s place and haul water from his garden house back to their house. Eventually they moved and did have a water line coming in, but even then, it wasn’t drinkable due to naturally occurring methane in the area water system.

Cloud is a member of the Southern Ute Indian Tribe, a relatively small tribe of 1,500 members, 1,000 of which live on the tribe’s reservation covering a little more than 1,000 square miles south of Durango abutting the border with New Mexico. Cloud’s experience is not uncommon in tribal homes across the country, as nearly 48% of them — representing more than half a million people — do not have “access to reliable water sources, clean drinking water or basic sanitation,” according to a 2017 congressional report.

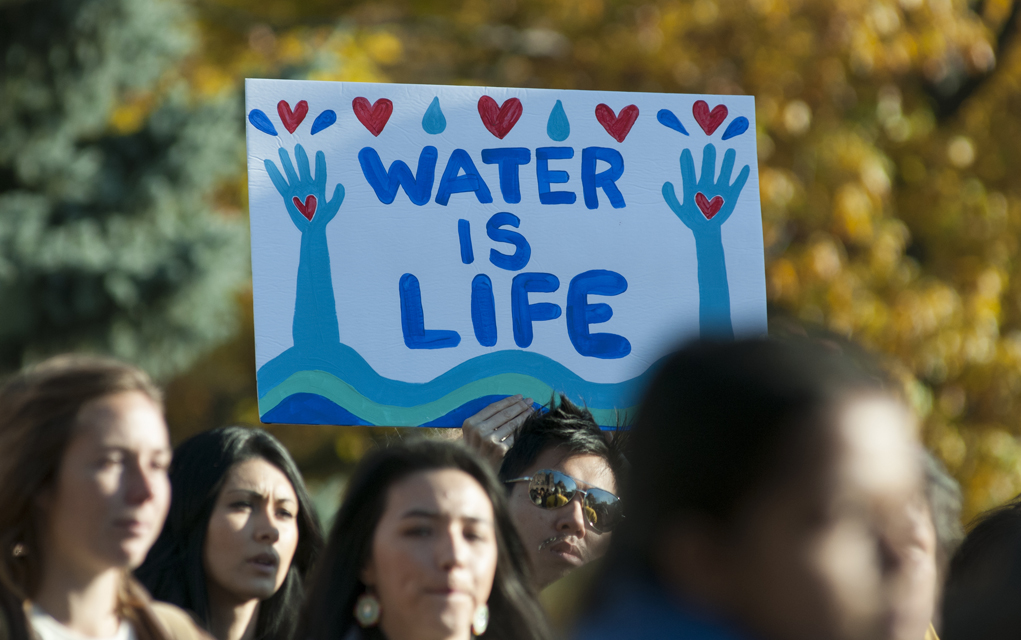

“In this day and age with all the technological advances, to acknowledge that there are still people in this country that do not have access to safe and quality drinking water and these people reside on reservations across the country is unfathomable,” Cloud told a virtual gathering of water and policy leaders in mid-December. The meeting was hosted by the Water & Tribes Initiative (WTI) to highlight the immediate need, made more urgent by the pandemic, for universal access to clean water on tribal lands within the Colorado River Basin.

“When we went into this work, we went with this premise that water is a human rights issue and that the federal government has a responsibility to ensure that native homes on the reservations have the same water access that any other American’s does in an urban setting,” says Heather Tanana, an enrolled member of the Navajo Nation and professor at the University of Utah law school. Tanana also has a public health degree and is working with WTI on clean water access.

The CDC reports that the coronavirus pandemic has disproportionately impacted Native Americans and Alaska Natives, with an infection rate 3.5 times that of the white population. Plus, Native American households are 19 times more likely to lack indoor plumbing than white households, Tanana says, quoting the U.S. Water Alliance.

“We’ve known about these problems for years, it’s not new,” Tanana says. “And the challenges that created them, we’re very well familiar with them.”

Read more here.